This lab is due at 11:59pm on 11/05/2014.

Please start at the beginning of the lab and work your way through, working and talking over Scheme's behavior in the conceptual questions with your classmates nearby. These questions are designed to help you experiment with the concepts on the Scheme interpreter. They are good tests for your understanding.

When you are done with lab, submit Questions 3, 4, 6, 7, 8 and 12 to receive credit for this lab. The rest are questions that are considered extra practice — they can downloaded by clicking on the button below. It is recommended that you complete these problems on your own time.

You can choose to do this lab either in your terminal or on this webpage. If you

choose to run this in your terminal, you can first download the lab08.scm file

by clicking on Generate Submission and work on it using STk. If you choose to

complete the lab on this webpage, click on Generate Submission after you

finish typing your solutions to download a file with your work in it.

By the end of this lab, you should have submitted the

lab08assignment using the commandsubmit lab08. You can check if we received your submission by runningglookup -t. Click here to see more complete submission instructions.

Scheme is a famous functional programming language from the 1970s. It is a dialect of Lisp (which stands for LISt Processing). The first observation most people make is the unique syntax, which uses Polish-prefix notation and (often many) nested parenthesis. (See: http://xkcd.com/297/). Scheme features first-class functions and optimized tail-recursion, which were relatively new features at the time.

You can also solve the following exercises with an interactive Scheme

interpreter right in the browser! Simply type Scheme code and press

Ctrl-Enter. Give it a try below:

If you choose to do this lab on your own computer, you can use the instructions below to install STk on your computer.

Our course uses a custom version of Scheme called STk. You can follow

these instructions to set up STk on your own computer. If you are

working on a lab machine (either physically or through ssh), STk is

already installed.

You can also download STk for your own computer. Make sure to choose the correct operating system (most likely Mac OSX, Windows, or Linux). For more information on installations specific to your OS, check Piazza for pinned posts!

If you are using Windows, the Scheme installer will install Cygwin, a UNIX-style terminal. To navigate to your files, do the following:

- Open up your Cygwin terminal (it should be on your desktop).

- Navigate to your libraries where you store your lab by typing

cd /cygdrive/c/Users. Typelsto see a list of users on your computer, thencdinto your user. (e.g.cd sally)- From here, you can navigate to your lab file as you usually do.

Let's take a look at the primitives in Scheme. Open up the Scheme

interpreter in your terminal with the command stk, and try typing in

the following expressions into the web interpreter to see what

Scheme would print.

> 1 ; Anything following a ';' is a comment

________

> 1.0

________

> -27

________

> #t ; True

________

> #f ; False

________

> "A string"

________

> 'symbol

________

> nil

________Of course, what kind of programming language would Scheme be if it

didn't have any functions? Scheme uses Polish prefix notation, where

the operator comes before the operands. For example, to evaluate 3 +

4, we would type into the Scheme interpreter:

> (+ 3 4)Notice that to call a function we need to enclose it in parenthesis,

with its arguments following. Be careful about this, as while in

Python an extra set of parentheses won't hurt, in Scheme, it will

interpret the parentheses as a function call. Evaluating (3) results

in an error because Scheme tries to call a function called 3 that

takes no arguments, which would result in an error.

Let's familiarize ourselves with some of the built-in functions in Scheme. Try out the following in the interpreter

> (+ 3 5)

________

> (- 10 4)

________

> (* 7 6)

________

> (/ 28 2)

________

> (+ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9)

________

> (abs -7)

________

> (quotient 29 5)

________

> (remainder 29 5)

________> (= 1 3)

________

> (> 1 3)

________

> (< 1 3)

________

> (or #t #f)

________

> (and #t #t)

________

> (and #t #f (/ 1 0)) ; Short-Circuiting

________

> (not #t)

________> (define x 3) ; Defining Variables

________

> x

________

> (define y (+ x 4))

________

> y

________To write a program, we need to write functions, so let's define one. The syntax for defining a program in Scheme is:

(define ([name] [args])

[body])For example, let's define the double function:

(define (double x)

(+ x x))When you define functions, you can load your definitions into Scheme by

entering stk -load filename.scm in your terminal, or if you have the STk

intepreter already opened up, you can enter (load

"filename.scm"), which will load in all definitions into your environment.

Alternatively, you can always use our Scheme Web Interpreter

here to test your functions

individually, just make sure to also paste in other dependencies you might need.

We've embedded the web interpreter into this lab so you can run your code

here. When you download lab8.scm above, all the code you typed into the

interpreters below will be in that file for you to submit.

In addition, we also define a testing function assert-equal, which tests whether an

expression evaluates to an expected value, which will allow us to run doctests

on the functions we write today.

When you are finished, running the following code (Ctrl + Enter) will run

all the doctests.

(define (cube x)

(* x x x))So far, we can't do much in our functions so let's introduce control statements to allow our functions to do more complex operations! The if-statement has the following format:

(if [condition]

[true_result]

[false_result])For example, the following code written in Scheme and Python are equivalent:

; Scheme

(if (> x 3)

1

2)

# Python

if x > 3:

1

else:

2Notice that the if-statement has no elif case. If want to have

multiple cases with the if-statement, you would need multiple branched

if-statements:

; Scheme

(if (< x 0)

'negative ; returns the symbol negative

(if (= x 0)

'zero ; returns the symbol zero

'positive ; returns the symbol positive

)

)

# Python Equivalent

if x < 0:

print('negative')

else:

if x == 0:

print('zero')

else:

print('positive')Define a function over-or-under which takes in an x and a y and

returns the symbols 'under', 'equals', or 'over' depending on whether x

is less than, greater than, or equal to y.

When you're done, run the following doctests!

(define (over-or-under x y)

(if (= x y)

'equals

(if (> x y)

'over

'under)))These nested 'if' statements get messy as more cases are needed,

so alternatively, we also have the cond statement, which has a

different syntax:

(cond ([condition_1] [result_1])

([condition_2] [result_2])

...

([condition_n] [result_n])

(else [result_else])) ; 'else' is optionalWith this, we can write control statements with multiple cases neatly and without needing branching if-statements.

(cond ((and (> x 0) (= (modulo x 2) 0)) 'positive-even-integer)

((and (> x 0) (= (modulo x 2) 1)) 'positive-odd-integer)

((= x 0) 'zero)

((and (< x 0) (= (modulo x 2) 0)) 'negative-even-integer)

((and (< x 0) (= (modulo x 2) 1)) 'negative-odd-integer))Now that we have control statements in Scheme, let us revisit a familiar problem: finding the greatest common divisor of two numbers. Let's try writing this problem recursively in Scheme!

Write the procedure gcd, which computes the gcd of numbers a and

b. Recall that the greatest common divisor of two positive integers

a and b is the largest integer which evenly divides both numbers

(with no remainder). Euclid's algorithm states that the greatest common

divisor is

In other words, if a is greater than b and a is not divisible by

b, then

gcd(a, b) == gcd(b, a % b)(define (max a b) (if (> a b) a b))

(define (min a b) (if (> a b) b a))

(define (gcd a b)

(if (not (or (= a 0) (= b 0)))

(if (= (modulo (max a b) (min a b)) 0)

(min a b)

(gcd (min a b) (modulo (max a b) (min a b))))

(max a b)))Ah yes, you thought you were safe, but we can also write lambda

functions in Scheme!

As noted above, the syntax for defining a procedure in Scheme is:

(define ([name] [args])

[body]

)Defining a lambda has a slightly different syntax, as follows:

(lambda ([args])

[body]

)Notice how the only difference is the lack of function name. You can create and call a lambda procedure in Scheme as follows:

; defining a lambda

(lambda (x) (+ x 3))

; calling a lambda

((lambda (x) (+ x 3)) 7)Write the procedure make-adder which takes in an initial number,

num, and then returns a procedure. This returned procedure takes in a

number x and returns the result of x + num.

(define (make-adder num)

(lambda (x) (+ x num)))Write the procedure composed, which takes in procedures f and g

and outputs a new procedure. This new procedure takes in a number x

and outputs the result of calling f on g of x.

Again, we have provided a few doctests for you to check your work!

(define (composed f g)

(lambda (x) (f (g x))))In Scheme, lists are composed similarly to how Linked Lists that we had

worked with in Python were implemented. Lists are made up of pairs, which

can point to two objects. To create a pair, we use the cons function,

which takes two arguments:

> (define a (cons 3 5))

a

> a

(3 . 5)Note the dot between the 3 and 5. The dot indicates that this is a

pair, rather than a sequence (as you'll see in a bit).

To retrieve a value from a pair, we use the car and cdr functions

to retrieve the first and second elements in the pair.

> (car a)

3

> (cdr a)

5Look familiar yet? Like how Linked Lists are formed, lists in Scheme are

formed by having the first element of a pair be the first element of

the list, and the second element of the pair point to another pair

containing the rest of list, or to nil to signify the end of the

list. For example, the sequence (1, 2, 3) can be represented in Scheme

with the following line:

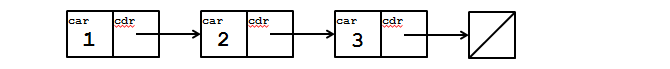

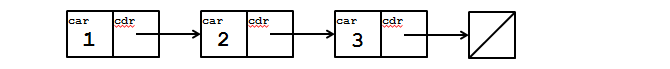

> (define a (cons 1 (cons 2 (cons 3 nil))))which creates the following object in Scheme:

We can then of course retrieve values from our list with the car and

cdr function.

> a

(1 2 3)

> (car a)

1

> (cdr a)

(2 3)

> (car (cdr (cdr a)))

3This is not the only way to create a list though. You can also use the

list function, as well as the quote form to form a list as well:

> (list 1 2 3)

(1 2 3)

> '(1 2 3)

(1 2 3)

> '(1 . (2 . (3)))

(1 2 3)There are a few other built-in functions in Scheme that are used for lists:

> (define a '(1 2 3 4))

a

> (define b '(4 5 6))

b

> (define empty '())

empty

> (append '(1 2 3) '(4 5 6))

(1 2 3 4 5 6)

> (length '(1 2 3 4 5))

5

> (null? '(1 2 3)) ; Checks whether list is empty.

#f

> (null? '())

#t

> (null? nil)

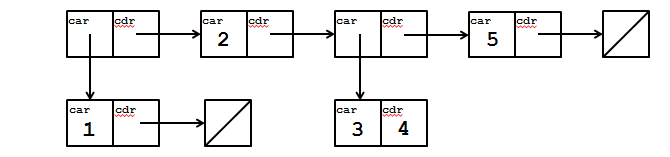

#tCreate the structure as defined in the picture below. You can enter your code here to check if it is correct.

(define structure

(cons (cons 1 '())

(cons 2

(cons (cons 3 4)

(cons 5 '())))))Implement a function (remove item lst) that takes in a list and

returns a new list with item removed from lst.

(define (remove item lst)

(cond ((null? lst) '())

((equal? item (car lst)) (remove item (cdr lst)))

(else (cons (car lst) (remove item (cdr lst))))))Create a function (filter f lst), which takes a predicate function f and a

list lst, and returns a new list containing only elements of the list that

satisfy the predicate.

(define (filter f lst)

(cond ((null? lst) '())

((f (car lst)) (cons (car lst) (filter f (cdr lst))))

(else (filter f (cdr lst)))))Implement a function (all-satisfies lst pred) that returns #t if all

of the elements in lst satisfy pred.

(define (all-satisfies lst pred)

(= (length (filter pred lst)) (length lst)))There's a lot to Scheme, which is perhaps too much for this lab. Scheme takes a bit of time to get used to, but it's really not much different from any other language. The important thing is to just try different things and learn through practice!

Fill in the definition for the procedure accumulate, which takes the

following parameters:

combiner: a function of two argumentsstart: a number with which to start combiningn: the number of terms to combineterm: a function of one argument that computes the nth term of

the sequenceaccumulate should return the result of combining the first n terms

of the sequence.

(define (accumulate combiner start n term)

(if (= n 0)

start

(combiner (accumulate combiner

start

(- n 1)

term)

(term n))))Remember the tree data structure that we built in discussion:

Write a procedure num-leaves that counts the number of leaves in a

tree.

(define (num-leaves tree)

(cond ((null? tree) 0)

((and (null? (left tree))

(null? (right tree)))

1)

(else (+ (num-leaves (left tree))

(num-leaves (right tree))))))